With everything else going on in the beer industry, the last thing it needs is drama from the Long Beach City Crew.

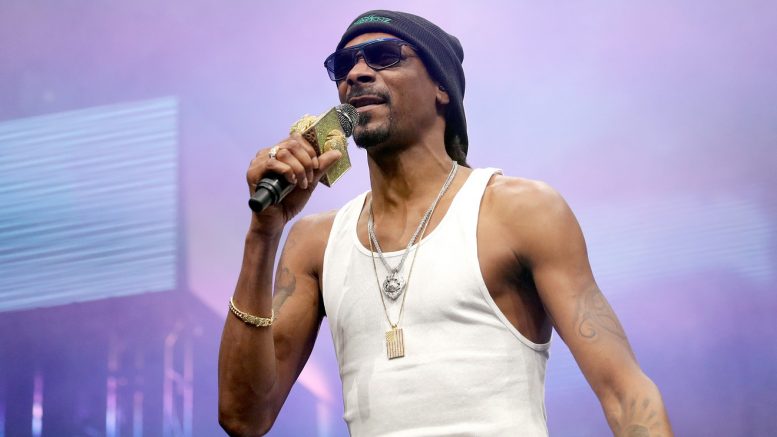

For much of the year, California rapper Snoop Dogg — or Calvin Broadus Jr. in the courtroom — has been attempting to get Pabst Brewing Co. to pay him the share of the profits he says it contractually agreed to when the brewery signed him to promote Colt 45’s Blast malt liquor brand in 2011.

When Pabst was sold by C. Dean Metropoulos to private-equity firm TSG and current Pabst Chief Executive Eugene Kashper for $700 million in 2014, Snoop claimed it triggered the “phantom equity” clause in his deal that entitles him to a 10% stake in Colt 45 — just one of the many holdings in the sprawling Pabst portfolio. However, Pabst claims that the sale, somehow, only transferred control of the brands and not ownership of them — basically saying that while someone new owns Pabst, Pabst retains ownership of Colt 45 (which it insists is key to the agreement).

Think that sounds a bit iffy? So did Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Malcolm H. Mackey, who denied Pabst’s motion for a quick summary judgment and excoriated Pabst’s attorneys by calling their argument “maddening” and saying they had “conjured up a lot of facts in this case.” The whole thing goes to a jury trial in October, but it’s already putting some lessons in place for U.S. brewers.

Put aside Uncle Snoop’s attachment to this. Put aside that his loan-out corporation — a legal entity that celebrities use for situations just like this — is called Spanky’s Clothing Inc. All of the above is just noise. The minutiae about branding, contracts and breweries as holding companies? Yeah, that’s all incredibly relevant in the modern beer business landscape.

There are about 4,700 breweries in the U.S., with thousands more in the planning stages. At the very beginning, when they’re just trying to establish themselves, open a brewery and pub, and get regular access to resources, they rely on various sources for capital. They take out bank loans and small-business loans, scrape together loans from friends and family, bring in investors and, in some cases, take private-equity firms’ money just to keep the doors open and fund growth as more folks walk through those doors.

Loans need to be paid back and private-equity investors expect returns on their investments. There isn’t a huge chance that Snoop is going to come walking through the door and do some publicity for your brewery in exchange for a stake when things get better. But there’s a chance that you’re going to make a promise to someone along the way.

In the wake of the big craft beer acquisition deals of the past few years, those promises can have big implications. When Full Sail Brewing Co. of Hood River, Ore., ran into financial trouble in the late ’90s after more than a decade in business, the brewery sold shares to 47 employees through an employee stock ownership program. In 2015, when San Francisco-based private-equity firm Encore Consumer Capital approached Full Sail with an offer, the deal those employees made in 1999 entitled them to both a vote on the matter and a share of the take once the sale was approved.

Breweries including Boston-based Harpoon, Odell of Fort Collins, Colo., and Deschutes of Bend, Ore., have all embraced at least partial employee ownership. But when you consider that 100% employee-owned New Belgium Brewing Co. in Fort Collins, Colo., is the eighth-largest brewery in the U.S. and is considerably bigger than both No. 10 Lagunitas and No. 17 Ballast Point — both of which were valued at $1 billion (or $300 million more than Pabst’s 2014 sale price) last year when Lagunitas sold a half stake to Heineken and Ballast Point sold outright to Corona’s parent company, Constellation Brands — that’s a whole lot of money owed to a whole lot of employees if New Belgium ever sells.

But at least it’s very clear who owns New Belgium. If Snoop entered a partnership with Magic Hat in Burlington, Vt., for example, would he be partnering with a company owned by Pyramid, Portland Brewing and Genesee owner North American Breweries, or would he be partnering with a brewery owned by North American Breweries’ parent company, Florida Ice and Farm, in Costa Rica?

If Snoop decided to become the spokesman for Victory Brewing of Downingtown, Pa., would he be working for their Artisanal Brewing Ventures partnership with Lakewood, N.Y.-based Southern Tier Brewing, or would he be working for its backers in private-equity company Ulysses Capital? Consider that the Oskar Blues, Cigar City, Perrin and Utah Brewers Cooperative (Wasatch and Squatters) breweries are now all rolled into the United Craft Brews holding company with Boston’s Fireman Capital serving as its majority owner. Would Fireman’s ownership be enough to trigger a “phantom equity” clause if Snoop was rolling fatties for Cigar City before they sold?

These are everyday questions for companies like Anheuser-Busch, Molson Coors Brewing Co.TAP, -1.52%Heineken N.V.HEINY, -0.02% and Constellation Brands Inc.STZ, -0.27%but now they bleed into those companies’ craft acquisitions as well. Between the four of them, they’ve acquired about a dozen craft breweries and cideries since 2011. Each of those breweries had obligations to meet and debts to settle, and all of that needs to be considered more than fine print in the final outcome. Basically, if you owe somebody a 10% stake in one of your brands for propping you up way back when, it’s something your buyers should be made aware of and something that a buyer’s legal team should be leafing through documents to find before anything like this is hammered out.

You may be inclined to write off Snoop Dogg’s claims as a TMZ blurb, but you do so at your own peril. With even craft breweries increasingly structured into rolled-up collectives and holding companies though acquisitions, Snoop’s case against Pabst could set a precedent for how breweries in those umbrella portfolios are treated, and how they can treat their employees, investors and contractors, in the future.

Don’t dismiss Snoop’s suit against Pabst just because he’s the guy who put out “Gin and Juice.” He’s about to teach everyone in the beer industry a lesson about how to conduct business amid a quickly changing landscape.

Jason Notte is a freelance writer based in Portland, Ore. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Huffington Post and Esquire. Follow him on Twitter @Notteham.

Source: www.marketwatch.com

Be the first to comment on "What Snoop Dogg’s Pabst Lawsuit Says About the Beer Industry"